On Saturday, February 14, 2015, my phone repeatedly rang in the middle of my lovely squash game. I cursed myself for not putting the phone on silent mode. I hesitatingly answered it. The distance caller said, “Prof, you are in the court playing, so you didn’t hear that Malam Falaki (as we fondly called him) is dead? He was assassinated.” Shockingly, my phone fleetingly fell out of my hand, momentarily confused. After confirmation, I witnessed Falaki’s burial in Kano on the same day.

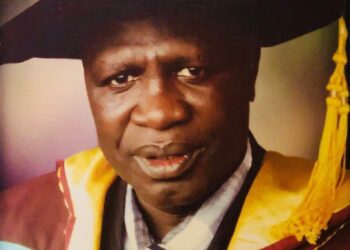

Today, Wednesday, February 14, 2024, marks the ninth year since we lost Professor Mustapha Ahmad Falaki through cruel and gruesome murder in cold blood by yet-to-be-identified assailants. My esteemed readers, I am dedicating my column this week to pay tribute to my excellent mentor, teacher, and Farmers’ General, Prof. Falaki, again. I am paraphrasing my earlier tribute, which was written some years ago.

Prof. Falaki mentored hundreds of us who passed through his arduous tutelage. He was a consummate agricultural scientist, extension specialist par excellence, and the Farmers’ General. It is difficult to justifiably describe the time and life of Prof Falaki. He embodied truth, hard work, and perseverance with a limitless passion for assisting, fighting for the common man, and engaging in youth mentorship. His relentless drive to support smallholder farmers earned him accolades nationwide and beyond. He was granted several chieftaincy titles from rural communities in many states as testimonies for touching their lives in agricultural enterprises.

He was a centerpiece of the Sasakawa Africa Association’s (SAA) enormous successes at its entry in Nigeria. Falaki worked assiduously with the first SAA Country Director, Dr. J. A. Valencia, and contributed immensely to developing Nigeria’s agriculture. He became the SAA National Coordinator in the early 2000s until 2009, when he handed over the mantle of leadership to his closest disciple, student, and ally, Prof. Sani Miko, as the second Country Director.

Falaki’s feats as SAA coordinator were groundbreaking, gargantuan, and unprecedented in Nigeria’s agricultural development history. When SAA set foot in Nigeria, the organisation was lucky to find a perfect match in Prof. Falaki, a simple, humble, and down-to-earth man with chains of disciples nationwide and an unquenchable urge to help smallholder farmers increase their productivity.

With the financial backing of Japan’s Nippon Foundation through SAA, Prof. Falaki’s team trained farmers on the “correct application of fertiliser” and good agronomic practices that impacted their productivity within the shortest time. Furthermore, farmers obtained credit facilities to purchase necessary inputs with more than 95 percent recovery. These short-term loans greatly assisted farmers in acquiring improved production inputs for timely utilisation, which increased farmers’ yield from an average of 1.2 tons/ha to 5.5 tons/ha.

Under Falaki’s wave of influence, SAA covered nine states; Adamawa, Anambra, Benue, Cross River, Gombe, Jigawa, Kano, Katsina, and Ogun. In these states, over 26,000 farmers, 3,800 extension agents, and lead farmers directly benefited from the SAA projects, which deservedly made Falaki the “Farmers’ General.” Prof Falaki’s roles as a teacher, school father, counselor, and mentor at Ahmadu Bello University (ABU) Zaria and other universities were very commendable and admirable.

This column cannot justifiably catalog Falaki’s inspirational, instrumental, and mentoring roles in making and shaping the lives and future of young men and women in ABU and beyond. Today, these men and women are doctors, professors, vice chancellors, and administrators, imparting knowledge and civility in the larger society as legacies from passing through the hands of the great personality, Prof. Falaki. To buttress this point, let me share my knowledge of this great icon with you.

In 1983, when I finished my A-level (IJMB), a one-year academic programme in the School of Basic Studies for direct admission into ABU, some of my classmates, although marginally qualified, only secured admission for their preferred courses through Malam Falaki, as he was then popularly called. When students had issues with admission, registration, accommodation, victimisation, and similar challenges, Falaki was always there with his magic wand.

His milk of human kindness continued to flow ceaselessly, his generousity was limitless, and his soft-spoken nature was so enticing and comforting to all of us. His humility, small stature, and friendly face made students free to reveal their worries. He was simply an epitome of hope to the hopeless and a darling tutor to all the students.

On employment after graduation, Malam Falaki was instrumental in employing several graduates who passed out with first-class and second-class upper-division degrees in the Faculty of Agriculture. Even as a relatively distant observer, I know some friends who secured employment courtesy of Falaki’s behind-the-scenes roles. Today, many of such friends have become full professors of various disciplines.

Although Prof. Falaki was from the stock of the so-called “Hausa-Fulani,” he was never discriminatory to people based on their religion or tribe. Professor Samuel Duru’s (may his memory be blessed) testimony is sufficient. He said, “Falaki was an Angel; he was a wonderful human being who often did the impossible; his absence during the faculty’s homecoming in 2017 was very glaring as he was missed by all the faculty’s graduates.”

Like many others, Falaki also touched my life. In 1998, when I was still a lecturer at the Federal Polytechnic Bauchi under the unbearable pressure of “Abachanomics,” one evening, I noticed a brand-new official vehicle parked in front of my house at the polytechnic’s quarters. I wanted to know who the august visitor was. Within a twinkle of an eye, Prof. Falaki emerged from the car, strode to the gate, and knocked.

I couldn’t believe my eyes; how could I entertain this important visitor? Do I dash to the neighbourhood to buy soft drinks? Why didn’t he send for me to come to his hotel as his peers usually do? I shivered and uttered, “Welcome,” after being persuaded to open the doors by his seductive smile and charming manner. He noticed that I was feeling uneasy and advised me to bring a mat outside so we could get some fresh air.

Prof. Falaki didn’t allow me to go out to buy any “entertainment”; he insisted on eating whatever we prepared for dinner that day. I was honoured to host such a great personality in my house, where the mere presence of a car symbolised opulence and “arrival” within the neighbourhood. After the dinner, Prof. Falaki brought out a letter. With a lovely smile, Falaki said, “This is your appointment letter to Ahmadu Bello University Zaria as an academic staff of NAERLS.”

“Babangida,” as Falaki called me, is a name only used by close family members and childhood friends. It was a moment of joy that remains a turning point in the entire history of my life. I later learned this was how Falaki visited some of his former students to deliver appointment letters, admission letters of postgraduate studies, or notes for them to deliver to other places to secure favours. It was just his typical passion to help others.

In the melee of the fight against Boko Haram, unknown criminals murdered Prof. Falaki before the very rural dwellers, the people he spent all his life serving. What an irony of life! May Ajannah Fildausi be his final abode, amen.